Your photo album might contain a whole lot more than just memories, and I’m not referring to the 14 attempts to get that perfect selfie either.

Dr. Yvonne A. de Jong and Dr. Thomas M. Butynski of the Eastern Africa Primate Diversity and Conservation Program are using photos to learn more about species and their distributions. To some, a picture of a cute monkey hanging from a tree branch might be in itself a good reason to capture the moment (obviously I didn’t hesitate).

However, after admiring the terribly adorable photo, the resourceful duo take a closer look.

It could be the white tufts of just-rolled-out-of-bed hair, or the absence of color on the belly that makes all the difference in the world in the species. By examining photographs taken in different geographic locations, the scientists are able to compare the phenotypic (or observable characteristics) differences between species/subspecies. While they admit that data derived from photographs cannot replace the role of museum collections in evaluating species variation, they are “a relatively fast, inexpensive, convenient, and unobtrusive means for detecting and assessing phenotypic variation within a species/subspecies over large areas.”

These photographic maps (or ‘PhotoMaps’) are free-access, and may come in handy for:

- identifying species/subspecies

- knowing which species/subspecies occur in which areas

- obtaining species/subspecies photographs

- confirming distributions

- describing species/subspecies variation with regard to geographic distribution

Here’s how it works.

Mary just returned from visiting her partner stationed on Zanzibar island as a Peace Corps Volunteer. After a morning at the beach the two visit Jozani Chwaka Bay National Park where she snaps a photo of an adorable (and a bit dweeby) red colobus monkey hanging upside-down rubbing the sleep out of its eyes. The vacation continues on, and for the moment the picture is forgotten. Not to worry, the photo isn’t going anywhere as the dweeby (albeit photogenic) monkey has already been immortalized as ones and zeros in her camera. Upon returning home to Lohrville, WI, Mary imports her vacation photos to her computer. She sees the picture of the little bugger and remembers a blog post she once read about contributing to primate conservation just by submitting photos. With just a couple of clicks Mary uploads her photo to the PhotoMap with a description of where it was taken. Mary feels good.

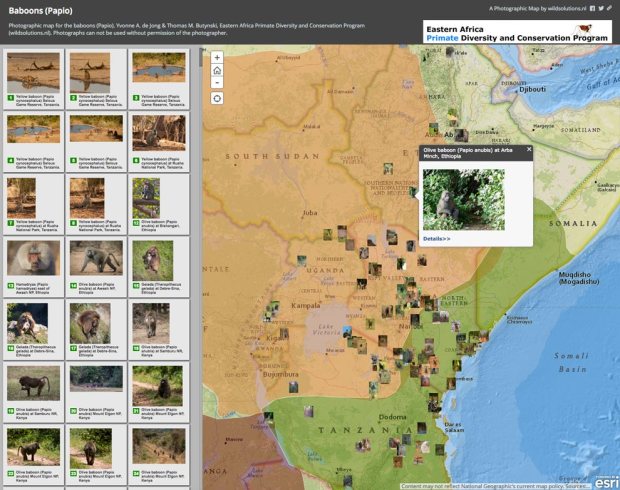

Mary’s story represents just one scenario. A truly beautiful aspect of this project, and others like it, is the use of technology to transcend international borders. In a world that desperately needs to begin thinking globally, such an opportunity creates a means for people to come together and help solve issues that we all have a stake in. Aside from the millions traveling to Eastern Africa every year to enjoy the rich cultures and diverse wildlife, people living in this region of the world naturally have the benefit of being ‘boots on the ground’ for such a project. Having contributed numerous photos myself, I found that talking to Ethiopian friends and colleagues in my town resulted in a torrent of information regarding where I could find these species (to photograph), or in some cases, photos that they had already taken! Note to PCVs – I would be remiss if I did not mention to any current (or future) Peace Corps Volunteers in the region that reaching out to other PCVs can be very productive as their sites cover large geographic areas, they are always snapping pictures, and if your group is anything like mine was – they travel a lot! (In fact, the photo of the olive baboon in the image below taken by fellow PCV Margaret!)

A summary found on the project’s website states, “these ‘living’ collections of geotagged images are a practical tool for documenting and discussing diversity, taxonomy, biogeography, distribution and conservation status and, therefore, for planning actions for conservation.”

As of March 2017, almost 3000 images have been uploaded to the 15 online PhotoMaps at wildsolutions.nl. In addition to African primates, the project also welcomes photos of warthogs, hyraxes, and dik-diks, especially ones that can help fill the ‘gaps’ in less documented areas (which can be determined by referencing the taxa-specific PhotoMap). Though like anything in science any quality data is good data and contributing what turns out to be the 40th submission of a red colobus from the Jozani Chwaka NP in Zanzibar definitely doesn’t do any harm. Although, I’m told any photos of giant forest hogs in Ethiopia are sure to turn some heads.

The only requirement is that each photo must be able to be placed geographically. Fortunately, many modern DSLR cameras and smartphones have integrated GPS technology which may record specific locality information as metadata the moment the shutter is released (this can usually be found in the details of the image file). If your camera does not support this feature, not to worry as citing the place (city [or proximity to], park, reserve, etc.) the photo was taken will do just fine.

Dr. de Jong comments on the project, “Until now, the PhotoMaps have certainly helped us to refine species/subspecies distribution limits. For various taxa we have been able to update the shapefiles (which represent their geographical range) used by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, the Mammals of Africa and other publications.” The fact that this project and others like it are used to inform the IUCN (the global authority on the status of the natural world) is a testament to the degree in which ‘ordinary’ citizens from around the world can impact conservation efforts.

All photos are tagged with the name of the photographer on the open-access website, though rest assured that visitors are not able to directly download the high resolution originals. If a viewer would like to view or use the photos for another reason, the authority remains with the photographer and must be contacted directly. Photographs and with accompanying locality information can be sent directly to yvonne@wildsolutions.nl. Furthermore, here is a little known fun-fact that all photographers should know: under the Federal Copyright Act of 1976 photographs are protected by copyright from the moment of creation. In other words, the instant you expose the film (or sensor for digital cameras) you are thereby the owner of the resulting image and control all exclusive rights, including the right to contribute to saving a species!